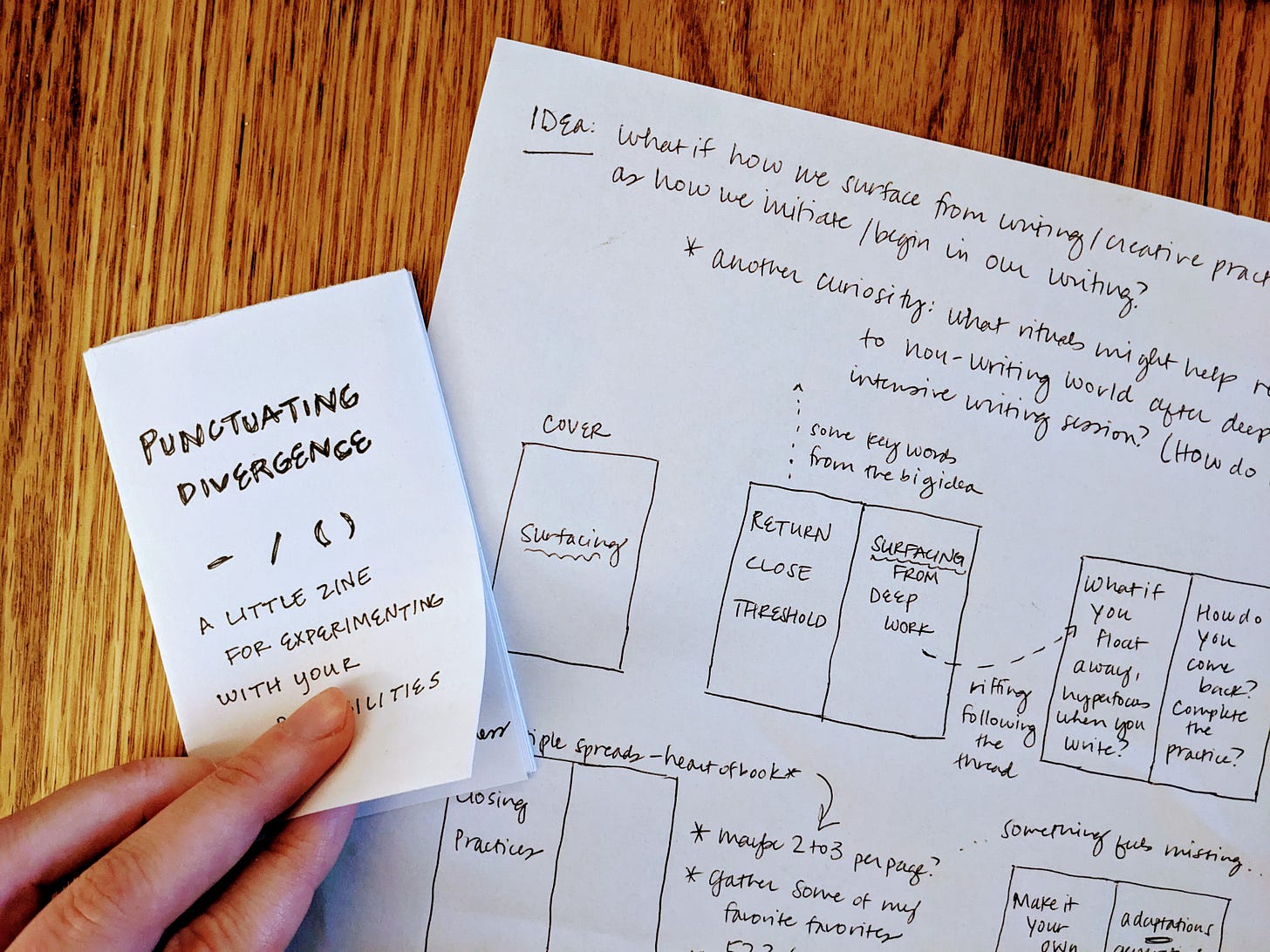

The video shows how I found my way into writing this post. I thought it might be fun to share how one nonlinear mind moves on paper before arriving in these linear sentences on a screen. I’ll share a second video in a later post, with details on how I’m playing with spreads for an upcoming zine.

I’ve been playing with zines lately, remembering how much I love them and imagining some new things I might share here (think: little curious books you can hold, fold, mark up, wonder with).

And because I’m so prone to observing the process and thinking about the thinking, the zine-making has led me down a rabbit hole of rediscovering that thinking in spreads is so much more interesting to me than other ways of thinking through. It’s especially more interesting than outlining.

Imagine a magazine open in front of you. There’s a headline, text, images in different spots and at different sizes (or maybe just one strong feature image), maybe a border or other element running across the two pages to tie them together visually. This is a two-page spread.

Spreads aren’t just a design tool—I like to imagine them as units of thought, or fields of thought.

If you’re more of a visual or swirling thinker like me, you might already know what I mean. When I have ideas, they aren’t linear, sentence-driven things. Sometimes I hear phrases/statements/questions, but in general, I’m not thinking in paragraphs or a linear progression. It’s more like fragments, pieces of setting or mood, images, and vibes… like a bunch of waves rolling at me, and sometimes I’m at the shore catching them, and sometimes I’m in the water feeling how choppy or soft or buzzy they are.

If I take that mind and immediately try to put it in the linear space of a word processor or the form of an outline, some combination of the following usually happens:

I forget fragments that I actually loved and meant to jot down.

I worry too much about what’s missing and don’t appreciate what I’ve already got.

I get pulled into thinking about the order of things instead of imagining the connections between things.

I plan the ideas more than I play with them.

I spend so much energy outlining that I lose interest in actually writing the thing.

But if I imagine the various pieces as parts of a two-page spread (or multiple two-page spreads), it gets easier and more interesting to move them around. I’m not trying to get things in the right order or make them too polished right away. I’m not vetting ideas.1 I’m just shuffling them around in an open field, imagining what it would be like to hold them across two open pages at a time.

I think this is why when I’ve got big ideas rushing in, I tend to grab a blank sheet of printer paper… I don’t go to lined paper, because this is something more like sketching or framing than it is straight-up writing. (Check out the video at the top of this post to see that in action.)

There’s something about the two-page spread that’s inviting in a way that other forms of thinking aren’t. Maybe it’s because with a spread, you literally have to open up to the pages, like opening a door.

Or maybe it’s because a two-page spread right-sizes and paces my attention.

When I’m reading a long post on a screen, I’m aware that I’ve been scrolling for awhile. I can sense when there is a lot of ground left to cover. Sometimes it feels like I’m digging, digging, digging toward the bottom of a hole.

Thinking and reading in spreads is inherently paced… and maybe it’s just more satisfying that way? The story or message might continue on the next page, but within the environment of the spread, you have everything you need for right now. And you’ve got the space to rest with it a little, to let it breathe.

As I’ve been building out spreads for new zines, I’ve been remembering:

Just because a book has a beginning, middle, and end doesn’t mean the path to creating a book has to be or feel that way.

Ideas are modular, spreads are modular, and modularity breeds possibility. I can rough out my ideas as two-page units, and then I can move and remix the spreads to play off each other (or not). Instead of perfecting at the sentence or paragraph level, I tinker at the spreads level, to notice which ideas support each other, contrast each other, sharpen each other.2 This keeps me in the space of play and expansion—and out of the weeds of over-editing too soon.

I can begin anywhere, because as long as the spreads are still in motion, there’s technically no “beginning, middle, end” anyway. Yes, I know you can copy and paste things to move them around in an outline too. But when my brain looks at outlines, it doesn’t see that. It sees an order of operations, not an open field. There’s no use fighting it—I’m never going to be an outliner. (The last time I tried was in 2020 with a project that I painfully over-architected and over-delivered on… the danger with outlines, for my neurodivergent bodymind, is not that I won’t think or do enough. It’s that I will think and do way too much. For me, thinking in spreads is like an insurance policy for enoughness.)

Thinking in spreads is just more fun. That’s probably all I really needed to write for this post: hey, this is fun, do you want to try it?

I’m convinced that many creative folks think they have a problem figuring out how to expand their ideas when the truth is they just vet themselves and their ideas too much and too soon. It’s easy to confuse vetting for editing. (Editing, later in the process, helps reveal an idea. Generally my sense is if something feels generative, let it flow. Vetting questions the idea and tends to have a less generative spirit.)

This is one way I figured out the flow of my first book, a collection of poems. Poems can be thought of as one long sequence in a collection, but they can also be thought of as companions working in sets of two (like meta couplets) on shared pages. In later stages of revision, I found that breaking the book into different units of thought like this can even help shake out the poems that really don’t belong in the book.

Video music is “Divine Life Society” by Jesse Gallagher.

Share this post